Failing Twice

/Journalist Jonathan Landrum on failure not being an indicator of your potential.

Jonathan Landrum dreamed of being a sports writer.

Until the star basketball player at his high school crumpled up one of his first stories in high school.

Jonathan was a sophomore at the time and had written a story for the school newspaper about the basketball game the night before, covering how his school’s team lost against a rival in the closing seconds.

The star player (who eventually reached the NBA and is currently an assistant coach for one of the league’s teams), read the game story and then crunched up the newspaper into a little ball, before leaving it on the table.

Like the newspaper, Jonathan was crushed; it took him years to realize the star player’s reaction wasn’t about his writing, but about the loss. If he’d known then that getting any kind of strong reaction was a good sign, he might not have been so discouraged.

But he was. So much so that when his high school teacher, noticing his writing talent, asked him to attend journalism camp that summer, Jonathan balked: “That's for nerds.” He’d given up on writing and was going all in on football.

But when he went to Highland Community College in Kansas then attended Clark Atlanta University on a football scholarship, he majored in mass media with the hopes of pursuing journalism.

And as part of his major, he took Basic News Writing.

He failed the class.

He took it again.

Then one day, his professor called him into her office. She told him honestly that he probably would not pass the class - again.

His professor asked him if maybe he wanted to consider another major. “No,” he said. This was the only thing he wanted to do. If that was the case, she said, if he was really serious, he was going to have to “hunker down and get to work, because you have a lot to work on when it comes to writing.”

He walked out of her office and kept on walking, pieces of the resolve he had in her office crumbling with each step.

After walking for a little while, he broke down and wept.

All he could think was:

“I need to quit.”

Then, he called his mom.

She said:

“You just have to continue to keep at it. You know what you're there for. I know you're better than that grade you just got. Now you just have to show them.”

Jonathan and his mom.

“That doesn't mean you need to stop running.”

With help from his mom, instead of quitting, he decided:

“Okay, let me try this again and see what happens.”

He signed up for Basic News Writing one more time, applied for (and got) a writing internship with Rolling Out magazine (he didn’t tell them he’d flunked Basic News Writing twice), and joined the college newspaper.

“So now it went from writing, maybe a story maybe once every three months, to writing 10 stories a week.”

He wanted to improve and thought the best way to do that was to write as many stories as he could. “It was a grind,” he remembers, “but it was well worth it.”

How did he go so quickly from failing a class twice and sincerely thinking about quitting to that level of commitment?

He shares that wanting to quit and actually quitting are two very different things. While he felt like quitting plenty of times, actually quitting “has never really been in my DNA.” He owes a lot of that to what he learned while playing sports:

“In sports, you're going to always fail at something. Someone's going to beat you in a race. That doesn't mean you need to stop running.”

He also cites the Clark Atlanta College motto: “I’ll find a way or make one.”

There were also a lot of people looking up to him - a sibling and cousins - and he didn’t want to let them down. But most of all, he didn’t want to let himself down.

“My heart wasn’t in it.”

Jonathan passed Basic News Writing on his third try. He passed Advanced News Writing too. And he thrived in his Rolling Out internship.

He also wrote a story about a football teammate from Haiti who inspired him, and that story won an award. And he was selected as one of 30 students for an LA Times sports writing workshop (where he was one of only three people of color in attendance).

As his writing experience grew, his football interest waned.

“I remember being at practice one day and I just didn't have the urge anymore; my heart wasn’t in it.”

The football player who once said journalism was “for nerds” had come back to his original dream. Writing became his passion. He also started to see more positive reactions from readers of his words.

“I went from a person who was a horrible writer, to someone who started to become pretty good. The more people started to recognize that and appreciate it, the more it gave me appreciation for it.”

He also freelanced in college, thanks to a professor who, seeing his dedication, connected him with a freelance opportunity with the Associated Press. He laughs as he remembers that when she first asked him, he’d never heard of the Associated Press and, as a “broke college student,” all he wanted to know was, “How much do they pay?” The answer was $50 an article, so he jumped at it. The stipend grew from there, as did his experience.

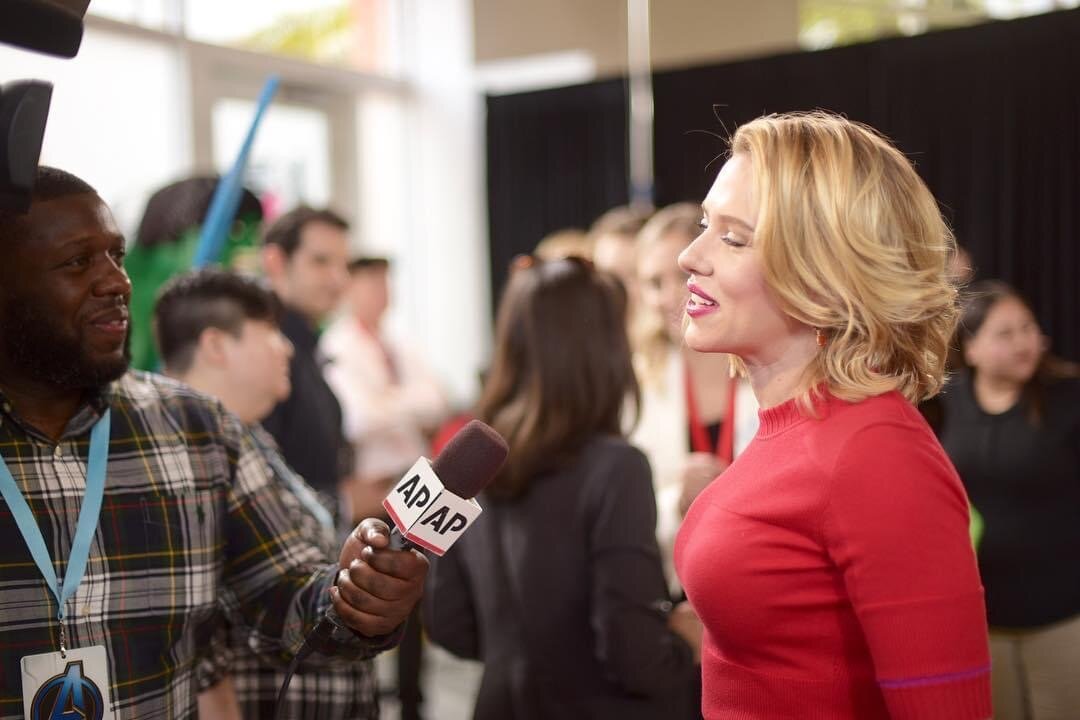

He covered local college events like basketball games at Morris Brown College and rallies at Spelman College. After graduating college he got a full-time job with the AP as an editorial assistant.

Jonathan parlayed the opportunity into a reporting one. He covered a variety of topics from sports to news to politics. Then one day, the music editor gave him an assignment to review a new album by R&B group Jagged Edge.

He loved writing that piece and thought he’d written “best music review known to man.” But then the music editor called him in and asked: “Jonathan, have you ever written a music review before?"

“No,” he said.

“Maybe you need to go read other music reviews, because you need to rewrite this."

“Dang,” he said, “I thought it was good.”

“Yeah,” she shared honestly, “this is not really all that good.”

He’d been here before. He knew what to do this time: “You have to look at yourself in the mirror and then figure out, okay, so what am I doing wrong?”

But just like before, it wasn’t that he was doing anything wrong; he just needed more practice.

He studied music reviews and then wrote it again. It worked. And he’s been doing that – interviewing, writing, rewriting – for the last 17 years.

Jonathan was asked to cover all kinds of stories in Atlanta, and has interviewed people like Tyler Perry, Robert Downey Jr., Big Boi and Andre 3000 from OutKast, Usher, Ludacris, Kevin Hart, T.I, DJ Drama, and Terrell Owens.

Some of those people even acknowledged him for what he wrote: “I've been able to build so many different relationships through my writing. It just encouraged me.”

“No, we’re still talking.”

Jonathan loves that he’s never stopped learning, something that’s kept him thriving in journalism all this time – because it’s required him to evolve over and over, as the media landscape constantly shifts: “I don't mind learning stuff. I'm like a sponge.” (Today, in addition to being the writer, he’s learned how to also be the photographer and videographer.)

A few years ago, Jonathan was offered a job to cover entertainment for AP in LA, where he gets to live out much of his childhood dreams. He regularly interviews A-list celebrities ranging from Brad Pitt, Leonardo DiCaprio, Spike Lee, Cardi B, The Weeknd, Jane Fonda, and Taraji P. Henson. He’s covered major events like the Oscars, Grammys, Emmys and Super Bowl. Even as an entertainment writer, he still ventures into the sporting realm interviewing popular athletes such as NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Damian Lillard of the Portland Trailblazers.

But the real dream come true moment, he shares, was bringing Oprah to tears (good tears).

He was tasked with interviewing her for a new show airing on her network, OWN: “Honestly,” he remembers, “I think I was supposed to have maybe seven minutes with her. That's what I was told.”

In the first minute, they talked about hangers.

Hangers? I ask, to be sure I heard him correctly.

Yes, hangers. It was small talk as she got settled into her seat. He asked her the best hangers to use for jeans, and she shared what she thought (wooden hangers).

After the hanger talk, Jonathan got into the interview, asking her about the new show, about working with Ava DuVernay, and about a groundbreaking film (“The Birth of a Nation”) he thought she might have an opinion on. He was right. When he asked her about it, she shared her thoughts and shed a few tears while doing so.

Once the seven minutes were up, Oprah’s publicist moved in to wrap up the interview - but Oprah stopped her and said, “No, we’re still talking. I'll tell you when we're done."

They talked for fifteen more minutes.

And when they finished, she turned to Jonathan and said, “You want to take some photos?”

He was floored. As a journalist, he never asks for selfies. But here Oprah was offering, asking him where his phone was. He pulled it out and she put her arm around him while they took a few photos.

“And then,” he remembers, “she was like, ‘Alright let me take off my glasses.’ I’ve got like ten different photos of me and Oprah."

“You cannot allow people to determine what you can or cannot do.”

In his 17 years as a journalist, Jonathan’s interviewed many artists and athletes at the top of their game; what has he noticed, I ask, about what they have in common, especially when it comes to what’s helped them get to that professional level?

“First of all, they're all in. There's a lot of hard work and dedication meshed with their talents.”

They also don’t seem to take any accomplishment for granted, having a keen understanding of the creative roller coaster they’re on, knowing that what goes up may always come down.

He's also noticed how much care they put into their creative relationships, understanding how valuable they are to growing, moving forward, and seeing new doors open: “Getting plugged in and connected to the right people can take you into so many different rooms.”

He remembers being one of the few (if not only) people of color in many rooms throughout his career. There has been some progression since then, he shares, but “we still have ways to go.” Especially, he shares, when it comes to paying journalists of color equally, and ensuring there are simply more people of color in media: “Those voices need to be heard.”

His voice, thankfully, wasn’t drowned out; mostly due to his own hard work and dedication, but also because of the teachers, the mentors, and the mother who believed in his voice all along.

How did that belief become his own, I ask, especially after that dark day when he really wanted to quit?

“When someone tells you no, that you can't, it does something to your psyche. But you cannot allow people to determine what you can or cannot do.

“If you feel in your heart of hearts that you can do it, you shouldn't have to stop. You shouldn't have to quit. Speak it into existence. Say it to yourself. Look in the mirror and say, ‘I'm going to go out there and kill it today.’ You have to have those conversations with yourself. If it's your will, it's your way. Then just go out there and do it. Keep pushing, always trying to progress.

“Ultimately, you'll get to the point where you feel confident in what you're doing, and you’ll know where you need to be - and which table you need to be sitting at.”

You can connect with Jonathan on Instagram or Twitter, and read his work at apnews.com.